Good Grief (OR: How to Cry on Your Mexican Vacation)

The first thing I noticed when I hopped into the Uber at Benito Juarez International Airport was how much everyone drove like my father. The cars on the highway (my driver included) swerved left and right as they jostled for the best lane, in the process weaving the etch-a-sketch tapestry that is chilango traffic. The aggressive but managed chaos of Mexico City’s drivers gave me the unexpected sensation of being at home. For a good half an hour, I could have been in the back of my late father’s car as he forged us a path through Bostonian gridlock. When home disappears, it winks at you from the most unexpected places.

Grief is our response to the disappearance of those we hold dear. Putting it so makes it sound incredibly simple—and in a way, it is. It’s a simple maxim: what is born must die. But to grapple with the unflinching cruelty that underpins life turns out to be immensely complicated. Who would have thought?

To grieve is to feel pain, an irrational and profoundly weird, life-altering pain. If you know it, you know it; if you don’t, you likely will in time. I think there are as many ways for an individual to feel grief as there are ways to mourn—some talk, some cry, some are silent. Some jump on the funeral pyre. But all feel pain. It’s universal. Even elephants mourn.

What’s nice is that no matter how you feel, you’ll probably have a lot of social codes to dictate how to act for your immediate future. There is pomp, drama and solidarity. Wakes, burials, speeches. Neighbors bringing food (I ate nothing but chicken ziti broccoli for a couple weeks). Long-lost relatives emerging from the woodwork. Obituaries and bereavement periods.

For most, after a certain time, the initial phase of immobilizing, gut-wrenching grief eventually subsides. You start to wake up and find that more often than not what was normal before feels normal once again.

Grief subsides, but it doesn’t go away as much as it evolves. Eventually, you hear the echo of the pain louder than initial thud. What is grief then? It’s an interesting question because its manifestations are much more subtle. I’m going to reflect a bit on what it is like for me.

I was often offered the metaphor of the wave to describe grief. It goes something like this: grief is a wave—it comes and goes, back and forth, rising and falling over and over again. It never goes away, but over time it becomes a smaller and smaller wave, and we learn to live with its motions, even if sometimes it comes crashing down out of nowhere.

I like this metaphor and found a lot of comfort in it when actively grieving the loss of my father. I’d like to add another metaphor to describe what it’s like to grieve years after the fact, to describe the scar left behind after the wound has healed.

I like to think of grief as being like déjà vu.

When you experience déjà vu, you are struck by the visceral feeling that you’ve already experienced an event, despite the impossibility to place the past experience anywhere in your personal history. This logical failing is of no importance—you feel that you’ve already had the experience. Some people say that it’s caused by our brain’s pattern recognition mechanism misfiring and convincing us that we have experienced a novel situation in the past. I’m agnostic about the cause (and deeply skeptical of most of cognitive scientists’ claims). I just know that the feeling is real.

I find that grief is similar. You go about your daily life, only to be affronted by what feels like nothing less than the real presence of the departed, despite knowing that they are not there and understanding the fatal impossibility of their presence. It’s like an echo from the grave that reverberates through your perception of the current moment. It’s like déjà vu, but instead of the unshakable feeling of a repeated event, you have the unshakable feeling of a repeated presence.

My father died a little more than five years ago. When the loss was fresh, he appeared to me everywhere, despite being, well, dead and buried in the ground. I saw him at the supermarket. I saw him in Renaissance paintings. I saw him in film screenings in the streets of Paris. He appeared to me in dreams, at times mundanely alive, at times as an inexplicable survivor of his own death (to my great surprise—How did I think you were dead?), forcing me to wake up and remind myself that he was, in fact, dead and not alive.

Sometimes I still hear his voice yelling at me to get out the bathroom!when I spend too much time in the shower. It’s uncanny.

I’ve found that the ghostly visitations and apparitions get rarer and rarer. We adjust. We move along. We learn to live our lives again, unburdened by the non-presence of the people who were once fixtures in them. It’s necessary and what everyone, I think, would want their loved ones to do after passing away. It’s certainly what I would want for anyone who loves me to do when I’m gone.

Grief becomes less like a punch to the stomach and more like déjà vu.

For me, every time I travel I feel my father’s presence. My mother worked for an airline in my teenager years, and thanks to her, my father, my brothers and I began to travel frequently. We visited Madrid, New Orleans, Washington, Ibiza, London, Paris…the list goes on. My brothers posted pictures of airplane wings to #flexonthegram. Family vacations were suddenly exotic and glamorous.

This was, of course, an incredible privilege in itself, but it also helped me and my father realize that, despite the constant fighting and endless disagreements that marred our relationship during my adolescence, we shared something: a love of travel. This shared interest was also highlighted by how much my brothers, constantly lobbying to stay in the hotel or lounge by the pool, were ambivalent about the whole thing after the initial pleasure of gloating to their classmates wore off (my brothers famously fought against going to Hawaii, San Francisco and Spain in favor of a road trip to Vermont).

After a particularly grueling week of arguing with my brothers (who were reticent to experience just about anything), my father and I were sat together in a Parisian bistro, having lunch alone. I was sipping on my first glass of wine with him (I was still a bit embarrassed to drink in front of my father—immensely ironic given his own lifestyle) and he was on his third cosmopolitan (a hilariously effeminate choice, ordered with zero hesitation) when he promised that our next trip would be just the two of us.

I was ecstatic. Yes, my brothers were incredibly annoying, but it wasn’t that. I relished in the underlying complicity of his statement. It felt like an initial thaw after years of freezing over. I left the trip imagining new adventures for us—both new places and a new, healthy, adult father-son relationship. Imagining a paternal love that I didn’t realize I’d missed until that moment.

I did not know that this would be one of our last conversations. I would say goodbye at Charles-de-Gaulle less than twenty-four hours later, and never speak to him in person again.

I think that this loss—of a positive, adult relationship with my father—is part of why I see him so much when I travel, why I could’ve sworn that I was with him while I pushed through Mexico City’s busy highways and (often labyrinthine) roads.

The way I experience this loss today leads me back to the concept of déjà vu. I don’t grieve in the same way that I did before, like a captain trying to steer a ship forward through a gargantuan wave. It comes in little bursts of presence, in moments where I can’t help but feel that my dad is with me. It feels like déjà vu, but with the feeling that someone who is no longer with you is in fact there. Travelling triggers it for me, I think because of my own regrets about what our relationship could have been like if we had just had a bit more time.

The grief that we carry on, if examined and experienced consciously, is an immensely powerful force for us to reconcile with death and the loss of those we love. After the initial pain has passed, it is how we honor the dead and allow them to live on in our memory. It’s beautiful, and even if it’s painful at times, I think it is worth it.

I may have travelled to Mexico by myself, but I like to think that I also went with my dad, even if only in spirit. Through all the lane changes, the endless Christmas decorations, the cold glasses of Coke, the Yuridia blasting over the radio and the endless escalators of a ten-storey Sears department store, I couldn’t help but feel that he was popping into my life again, even if just for a minute, even if just to say to say Wow!

If you saw me crying by myself on the streets of Mexico, don’t feel too bad for me. I was just having déjà vu.

Some reflections on how my dad would’ve found in Mexico City that I noted in my travel diary:

- He would have loved the food. One of his favorite things to do while travelling was to eat at the same places as locals—is there a better place to do this than Mexico City? If there is, tell me.

- Little memory: When we were in Madrid, we walked for about an hour before stopping at a random churro place by the highway. He asked for milk to accompany the churros and hot cup of chocolate, only to be immensely disappointed that it was delivered warm. This later became a highpoint in his retellings ‘We ate breakfast with real workers, regular people’).

- Bisquets Obregon would have been a certain highlight.

- He would 100% come home and tell everyone that Mexican Coke is superior.

- He would have asked everyone what they thought about Claudia Sheinbaum (and if they were positive he would’ve said what a big fan he was).

- The Mexican love for Christmas would not have been lost on him.

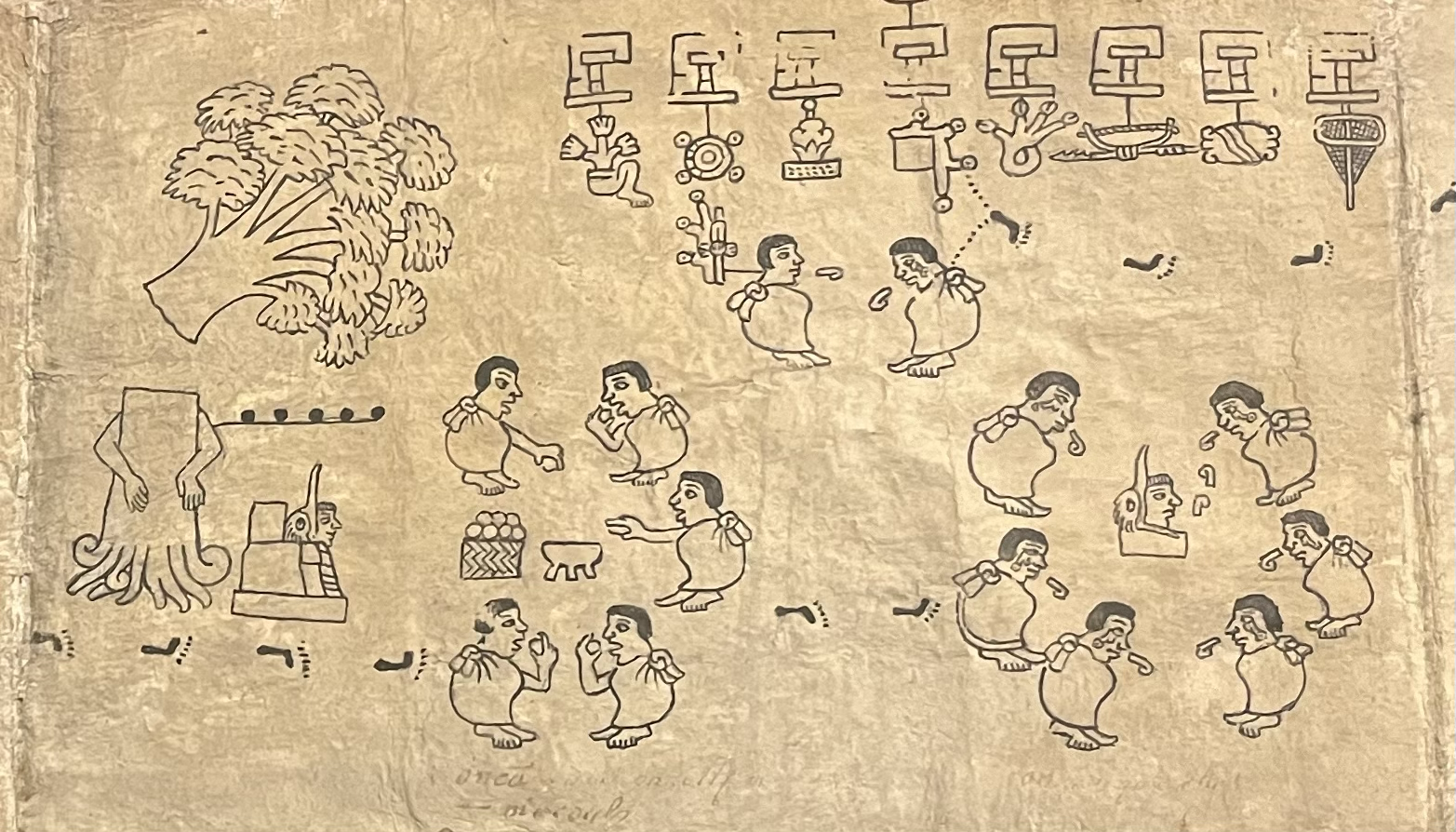

- He loved ancient history and would have been obsessed with the Teotihuacan temple complex. He was obsessed with Stonehenge, and this was leagues better. You get to walk around and touch things. It breathes more.

N.B.: I used the French spelling for déjà. Je ne supporte pas de l’écrire sans accents, sorry.